Bloomberg review cites Loeffler’s “trailblazing” work

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2023-12-21/how-modernist-architects- fought-communism-in-the-cold-war?srnd=premium

Saving the Architecture of Cold War-Era Diplomacy

US embassies built after World War II were designed to showcase American values and combat communism. But the future of these modernist landmarks is uncertain.

By Mark Byrnes

December 21, 2023 at 8:00 AM EST

When Eero Saarinen’s US embassy in Oslo, Norway, recently reopened as office space after a careful and costly restoration process, the building’s rebirth represented an uncommon historic preservation victory. Many other decommissioned embassies built in the early years of the Cold War face very uncertain futures. Created in support of soft diplomacy during a time where spies, not terrorists, were keeping US officials on edge,

these impressive complexes now find themselves out of step with the post-9/11 security landscape.

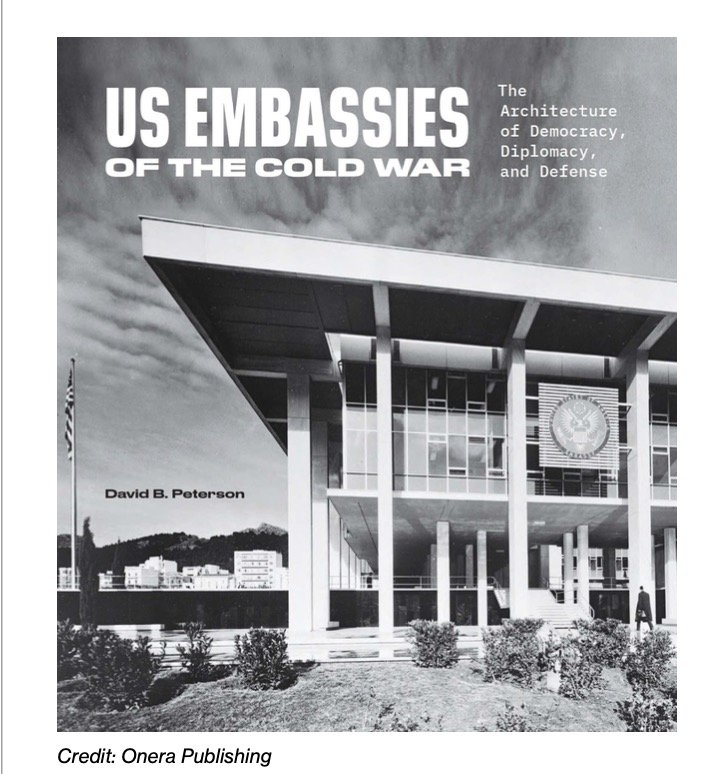

A new book by David B. Peterson, US Embassies of the Cold War: The Architecture of Democracy, Diplomacy, and Defense, provides fresh insight into how the US State Department sought to use modernism as a tool of statecraft immediately following World War II. Building off of Jane Loeffler’s trailblazing 1998 book The Architecture of Diplomacy, Peterson tells the story of the Office of Foreign Buildings Operations, which launched a series of ambitious architectural commissions between 1945 and 1961. During that period, the FBO (now known as the Bureau of Overseas Buildings Operations), commissioned more than 25 embassies, built to be “billboards for democracy” in countries seen as susceptible to the influence of communism.

The FBO hired prominent architects like Saarinen (who had previously done highly secretive war-related design work for the US government), Edward Durell Stone, Marcel Breuer, Walter Gropius, John Johansen and others, to build centrally located, inviting places that demonstrated — inside and out — Western democracy’s enlightenment and superiority. These embassies were not

only offices for diplomats (and CIA agents), but destinations for locals to come in and check out a book, watch a movie and take in an art exhibit.

Accordingly, most of these structures hosted multiple entrances along easy-to-access city streets, rendering them vulnerable to the eventual rise of global terrorism. After Al- Qaeda’s bombings of the embassies in Nairobi and Dar es Salaam in August 1998, later

buildings were far less porous. An additional focus on cost controls during the George W. Bush administration led to the disbanding of the Architectural Advisory Committee in 2004. So bad were the resulting buildings that in 2009 then-senator John Kerry proclaimed, “We are building some of the ugliest embassies I’ve ever seen. We are building fortresses around the world. I cringe when I see what we’re building.”

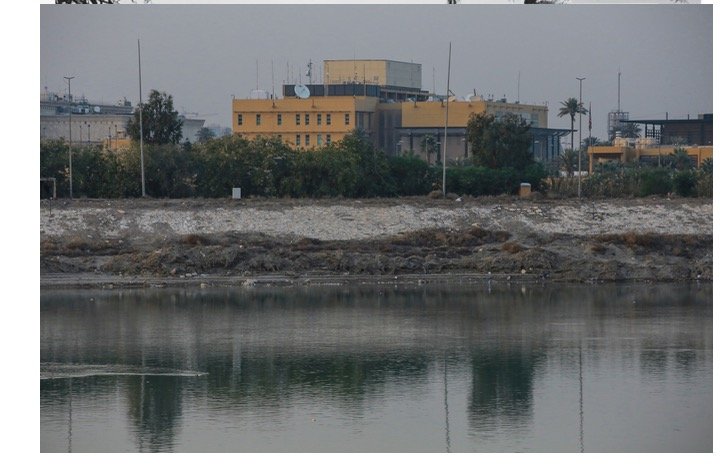

Today, US diplomats work out of a gargantuan 104-acre compound inside the fortified Green Zone.

Perhaps no city provides such an extreme devolution in American embassy design than Baghdad. America’s first embassy in Iraq’s capital, designed by Josep Lluís Sert and built in the late 1950s, was widely praised for a series of terraced courtyards that, Peterson writes, “put the State Department’s emphasis on openness and transparency on vivid display.” It was abandoned on the eve of the Gulf War of 1991. Today, US diplomats work out of a gargantuan 104-acre compound inside the fortified Green Zone. On top of its prison-like design and exorbitant construction and operational costs, the 21-building embassy complex also cuts off public riverfront access.

Josep Lluís Sert’s modernist US embassy in Baghdad was built in the 1950s to embody American ideals.Source: US Department of State, courtesy of the National Archives

Its 2009 replacement is a massive fortified compound that stands as the largest US embassy in the world, and perhaps the ugliest.Photo: Ameer Al Mohmmedaw/picture alliance via Getty Images

Even in friendly territory, contemporary embassies can be architectural disappointments. KieranTimberlake’s new US embassy in London, born out of the OBO’s 2010 Design Excellence program, may be more attractive than the crop of buildings that Kerry decried, but local observers have criticized its extensive defensive features. (In 2017, Bloomberg CityLab’s Feargus O’Sullivan wrotethat “the building floats unreal and detached above its surroundings looking every bit the gun-protected sanctum it is.”) Meanwhile, Saarinen’s decommissioned embassy in Grosvenor Square is being converted into a hotel where — unlike in Oslo — the interiors have been stripped away despite their landmark status.

Eero Saarinen's US embassy in London is being transformed into a hotel. Source: US

Department of State, courtesy of the National Archives.

Peterson laments the state of so many of the embassies in his book, but he sees reasons for optimism. Stone’s embassy in New Delhi is among the rare Cold War-era buildings still used for its original purpose; it’s now undergoing a thoughtful renovation and restoration by Weiss/Manfredi. And new constructions by Studio Gang for an

embassy in Brasília and Tod Williams Billie Tsien Architects with Davis Brody Bond in Mexico City show that ambitious architecture still has a role to play in international diplomacy.

Bloomberg CityLab recently spoke with the author to find out how America’s Cold War embassies came to be and just how unique the program was. The interview has been edited for clarity and length.

What was the typical US embassy like before the Cold War?

There were very few traditional embassies. A typical one was a rented space and in fact, outside of some of major cities like London and Paris, you might find a US embassy above a garage or a repair shop, like in Karachi. World War II changed all that. The US quickly built embassies starting under the Truman administration, establishing a real presence throughout the world, particularly in South America. These buildings were used by the CIA — the point was to have eyes and ears in places where they thought something troublesome could happen.

How did the public component compare to what the US would do for a World's Fair Pavilion?

Democracy competed with communism in many different ways, including architecture and culture. The World’s Fair pavilions had the same idea of portraying Americans as the embassies did. In fact, for the 1958 fair in Brussels, Ed Durell Stone’s design for the US pavilion was basically a circular version of the embassy he did in New Delhi, which opened in ’59. The Soviet Union was building, particularly at the time of the exhibition, more neoclassical-like, oversized, powerful buildings that portrayed a country of military might, not accessibility.

How did the State Department get these embassies built?

It was a very informal process and they were very creative with financing. They relied on foreign governments who owed the US under the Marshall Plan to pay for buildings and sites. America had a Lend-Lease and credits in Europe after World War II and those countries did not want to use hard currency in repayments, so they got materials instead. The embassy in Havana, for instance, was built with travertine marble from Italy.

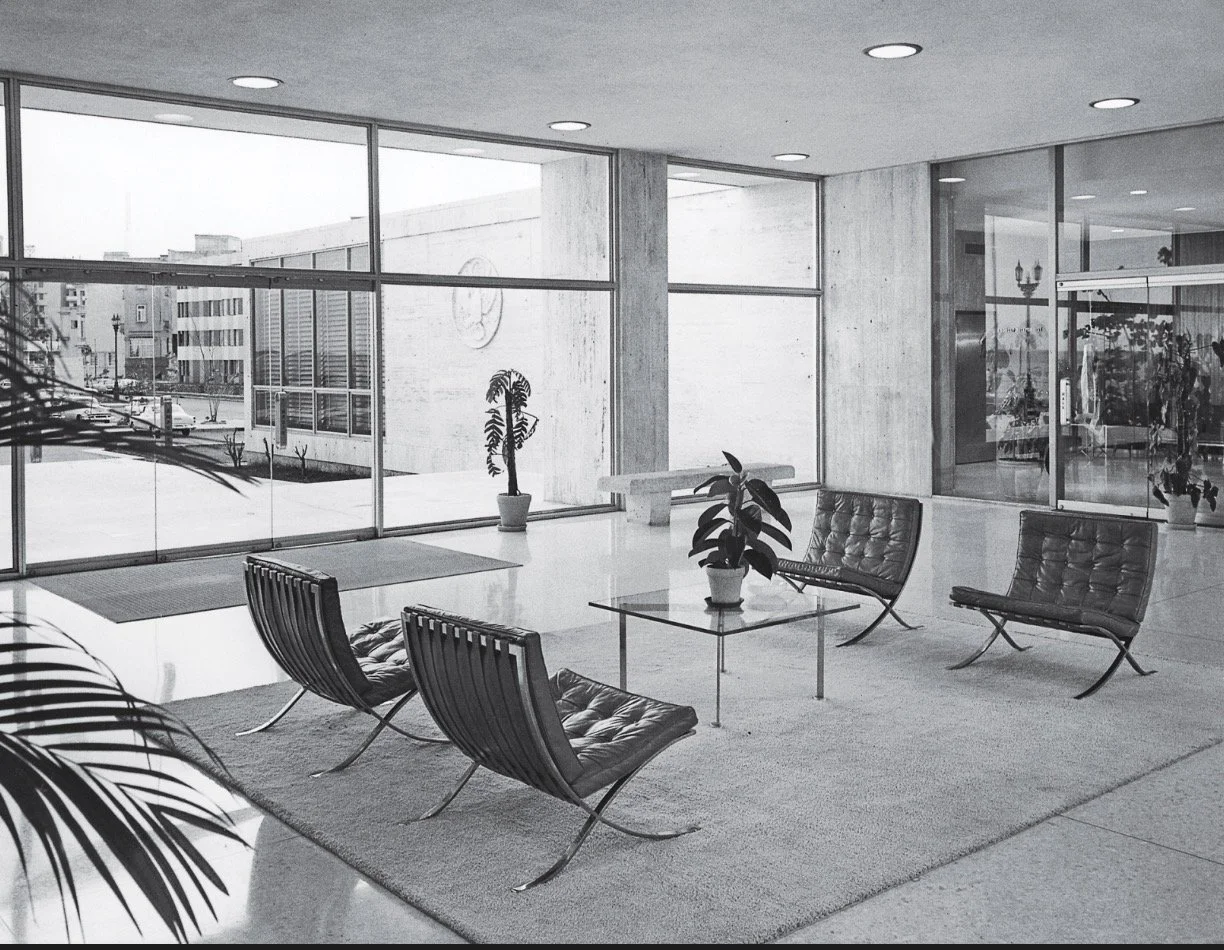

The interior of the US embassy in Havana, designed by Florence Knoll, shows off its mid-century style, complete with a set of Mies van der Rohe’s Barcelona chairs.Source: US Department of State, courtesy of the National Archives

The early part of the building program was not well organized but it became more formal. There was an architectural review board with very talented architects on it. It lasted for half a century, until it was canceled in 2004.

Besides a general shift from International Style to contextual modernism, were there any other key differences between a new embassy designed during the Truman administration and one during the Eisenhower administration?

Truman and Eisenhower were thinking a lot more about the threat of communism than architecture, but the State Department attracted a lot of very good people for these new embassies during both administrations. No other country was building embassies like the Amercians were. It was all about the FBO. They basically had free rein for about six years. Then the criticism started.

There was some heat from certain congressmen who felt that the International Style was a little too modern and experimental. Even Florence Knoll’s furniture at the embassy in Havana was criticized for being too modern.

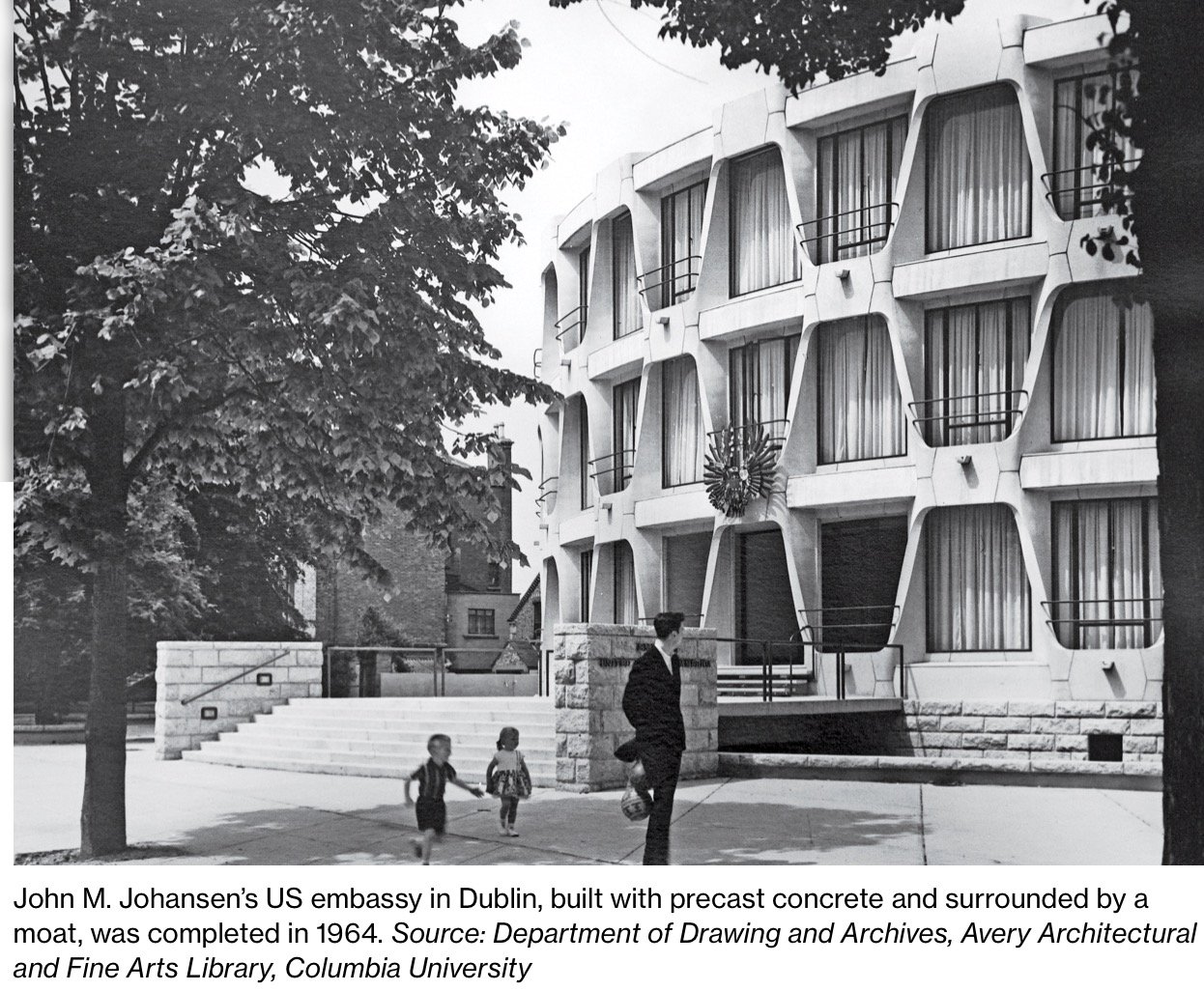

There were a lot of bumps along the way. The time from design to completion was often four to five years. In fact, Dublin’s almost never got built because Congressman Wayne Hays didn’t like the design and stepped in. It took President Kennedy to write a personal note to the congressman in 1961, saying that they needed to go ahead with the design. It’s a good example of contextual modernism, a Celtic-inspired design, very Irish. It was a challenging triangular site but it resulted in a great building. John Johansen deliberately made it circular as a message: America never turns its back on anybody.

Did the Soviets have anything comparable?

Cuba was one of the biggest Cold War battlegrounds. The US embassy in Havana was an International Style building by Harrison & Abramovitz, while the Soviets

responded with something that is almost laughably symbolic of their totalitarian image.

If you look at the UN building in Manhattan, it is not dissimilar to the US embassy in Havana with its flat roof, curtain wall, significant glass and lack of ornamentation. It’s very clean and transparent. In Athens — the birthplace of Western democracy — Walter

Gropius designed the US embassy with the same Pentelic marble as the Parthenon. To me, those are the truly American buildings of this program. They became more contextual to their local surroundings later on.

Walter Gropius borrowed from the Greek Parthenon to create the US embassy in Athens.Source: Harvard Art Museums

What elements of these embassies would be the most shocking for a younger person to discover, compared to the embassies that were built with terrorism in mind?

Unless you’re of that era and you actually went into the embassies, you probably wouldn’t know that there were three separate entrances. One was for the diplomats, one for visas, and a third for cultural diplomacy — the soft power stuff. That’s where you’d go to access the auditorium and the library. At one point, the embassy in London had over 100,000 visitors just for the library.

After World War II, the US threw everything it had at containing and defeating communism. Architecture was one way and cultural diplomacy another. The USIA , which was sponsored by the CIA, made a big effort using cultural activities for their public diplomacy initiatives. A lot of those things took place inside embassies. But if you go to an embassy now, you’ll find no library, no theater, no broadcasting room. There's nothing you can learn in an embassy today.

A metallic mural by American artist Harry Bertoia decorates the facade of the US embassy in Caracas.Source: Docomomo Venezuela

A lot of these decommissioned embassies you featured in the book seem to at least be viewed locally as having some cultural value, including in countries that have very precarious or hostile relationships with the US today.

You've got to go country by country.

London is not one of those even though the UK is one of America’s best allies. Saarinen’s building was decommissioned and sold a

number of years ago to the Qatari investment fund to become a mixed-use development. The facade was kept but the interior was demolished. It was one of the great sites in London, on Grosvenor Square. It could have become some kind of American information center, a nod to the importance of the relationship between England and the US, particularly during World War II.

Of these buildings that are still functioning as embassies, what about their design or location allows them to carry as originally intended?

They're hanging on by their nails. Five or so of the original 25 Cold War embassies should remain for now. Dublin’s is probably the next to be decommissioned because it’s such a vulnerable site. These buildings were built to be open, accessible and transparent but architecture cannot lead the way. We live in a different world now and security has had to come first.

Eero Saarinen’s US embassy in London is being transformed into a hotel. SEE PHOTO ABOVE. Source: US Department of State, courtesy of the National Archives

In London, they tried for years to protect the Saarinen building adequately. Thank God nothing bad happened, but they put up bollards, shut down streets, and added more security in the area.

That’s all fine temporarily, but it was driving the neighbors crazy and how could you blame them?

There at least seems to be a renewed emphasis on architectural design now and a belief that quality architecture and security aren’t necessarily mutually exclusive. It’s not that I’d like to see KiernanTimberlake’s design for the embassy in London repeated all over the world, but it is a strong attempt to do something a little bit different, something architecturally adventurous. We’re seeing good architects now who are striving for design excellence rather than just making defensive architecture. A new embassy going up in Mexico City by Tod Williams Billie Tsien Architects and Davis Brody Bond looks promising. I’m excited about the new embassy in Brasília by Jeannie Gang. I’m encouraged by what's happening.